Mike Bacidore is the editor in chief for Control Design magazine. He is an award-winning columnist, earning a Gold Regional Award and a Silver National Award from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. Email him at [email protected].

Imagine the gains in productivity and profitability you’ll realize when you connect machinery to the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). More information means smarter decisions. And collective intelligence is better than siloed data.

Are you ready to share your data? I’m not talking about the cloud. I mean opening your data and your network and your controls available to anyone with a desire to access them.

Maybe someone in China or Russia has an interest in your equipment and controls. Maybe it’s the same individuals who were able to hack the U.S. federal government’s systems.

If you think you’re secure, you definitely are not.

A defense-in-depth strategy is a must, but that’s just to keep out the riff raff. The first rule of cybersecurity is to assume you will be breached. But how vulnerable are industrial computers to these threats?

“Cyber risks exist anywhere a connected asset exists, whether that asset is an industrial computer or another type of device,” explains Doug Wylie, CISSP, director, product security risk management, Rockwell Automation. “Cyber risks from both internal and external sources expand with each new connection. They create threats capable of disrupting not only specific devices, such as an industrial computer, but also the systems to which these devices connect. This includes potentially affecting control system operation, safety, productivity and the ability to protect assets, machinery and information. These threats have the potential to strike at the heart of a company’s reputation and its long-term viability.”

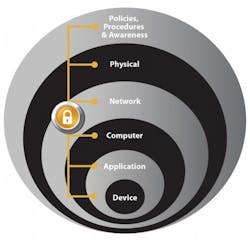

Figure 1: Protecting assets, including industrial computers, requires a defense-in-depth security approach to address internal and external security threats.

No single product, technology or methodology can fully mitigate cyber risks, says Wylie. “Protecting assets, including industrial computers, requires a defense-in-depth security approach to address internal and external security threats (Figure 1),” he says. “This approach utilizes multiple layers of defense—physical, procedural and electronic—by applying policies and procedures that address different types of threats—for example, multiple layers of network security to help protect networked assets and multiple layers of physical security to help protect high-value assets.”

Cybersecurity inhabits the day-to-day thoughts of manufacturers, and rightly so, as more and more data is stored and transmitted through cloud-based information systems, says Daymon Thompson, TwinCAT product specialist, Beckhoff Automation. “Fear surrounding hacking and data breaches has caused hesitance by some to adopt more connected information management tools,” he explains. “This is a giant mental block that can neutralize innovation, preventing some machine builders from implementing Internet of Things and Industry 4.0 concepts for smart factories. Today, extensive research, testing, and improvements are pushing security best practices to the forefront, helping assure that industrial data is kept safe.”

Machine security can be divided into three categories—direct local access, indirect local access and remote access, says Thompson. “Direct local access means that a potential attacker physically interfaces with the computer and interacts with it via attached input devices, such as a USB flash drive, mouse or keyboard,” he explains.

“Indirect local access means that the potential attacker cannot directly, physically interact with the device but has infiltrated the system by other, non-physical means. Remote access refers to a scenario in which a cyber criminal tries to attack the industrial controller from a remote location, such as through the local network. Network connectivity could provide a potential cyber criminal with more ways to compromise system security, as industrial controllers are becoming more and more connected to systems that reside in other connectivity layers, such as SCADA, MES systems or even the cloud.”

Measures to maintain secure connected platforms include proper firewall settings, using secure protocols such as OPC-UA to move encrypted data to the cloud, and locking down local USB ports, offers Thompson. “There are also a large number of working groups focused on industrial security who can offer a wealth of additional information and recommendations,” he says. “The National Institute of Standards and Testing (NIST) offers a cybersecurity framework, created through a year-long collaboration between NIST, industry, academia and government stakeholders. NIST continues to curate this framework, providing updates and improvements as necessary to maintain high levels of security. Global framework standards, such as ISO/IEC 27001, exist as additional means to provide guidance when performing risk assessments and implementing security strategies.”

Another aspect of security is protecting intellectual property (IP) held within the control system software, explains Thompson. “This is undoubtedly the most valuable technology in your machine design,” he says. “Cybersecurity should no longer prevent machine builders from implementing their most innovative ideas for highly-connected machine technology. Protection of intellectual property and sensitive company data is a real concern that has been addressed here and now with intelligently designed PC-based control software. By leveraging the currently available security tools and code-management processes, machine builders can be ahead of the game and fully implement their connected machine designs. Following published guidelines, leading machine builders can now ideally complement the modern smart-factory concepts of their end users, while minimizing security risks at the same time.”

Industrial PCs (IPCs) are very vulnerable and one of the weakest points inside an industrial network, says Mariam Coladonato, product marketing specialist, networking and security, Phoenix Contact USA. “We know industrial control systems to be continuous in nature,” says Coladonato. “This is the reason why a large number of legacy IPCs are still deployed in active control and monitoring roles. Most of these are running an older, out-of-support operating system, such as Windows 2000 or XP. Although many vulnerabilities and flaws remain open, Microsoft no longer provides patches or service packs for these old operating systems. This leaves these devices susceptible to security risks such as worms, viruses and other cyber attacks.”

To protect the PCs, start with operating-system updates. “Taking the time to keep your systems patched and updated is a non-technical, although potentially time-consuming, step that any control engineer can do,” says Coladonato. “Another step can be adding some type of antivirus in the computers; it can be white- or blacklisting, depending on the user's perspective.”

Traditional antivirus operates in a signature-based system, in which the engine compares files and activities to a known database of virus signatures. “If it finds a match, it then deletes or quarantines the offending file,” explains Coladonato. “This model brings some limitations—for example, each computer inside the industrial network has to have a unique license, making it more expensive. Also, this database needs to be updated frequently to detect and protect against new viruses.”

One approach to protect the IPC files is through common Internet file system (CIFS) integrity monitoring. “The hardware/software works by first taking a baseline snapshot of the selected operating-system directories,” explains Coladonato. “Next, it’s set to periodically scan the chosen files. If any of the operating-system files have been modified or deleted, or if any new file has been added to the monitored directory, an alert is generated in the form of email, SNMP trap or log warning. At this point, corrective actions can be taken by engineering, maintenance or IT staff. This solution can be more cost-effective because one scanner can monitor multiple PCs.”

Information technology (IT) and operations technology (OT) networks are managed with different priorities in mind and each has distinct security needs, explains Pocheng Chen, director, embedded software, Advantech. “IT was traditionally associated with back-office business systems, with the purpose of protecting data confidentiality,” says Chen. “Traditional antivirus software can scan your computer for viruses and other malicious software, helping to remove or contain threats. OT is traditionally associated with field devices and the systems to monitor and control them such as SCADA. An OT network needs secure access to ensure data confidentiality and physical safety, especially in factories. It’s important to build a mechanism or enhance devices or systems to guard against threats that may inhibit legitimate protocol functions, such as restarting or turning devices off.”

Attacks on industrial controls are on the rise, says Richard Clark, technical marketing specialist, InduSoft, Schneider Electric Software. “There are many documented instances of cyber attacks on industrial control systems from a number of sources,” he explains. “The information that has been gathered and aggregated has been mostly from honeypots or credible attacks on existing systems, established and investigated by government labs like Sandia and Idaho National Laboratory, home of ICS-Cert, and by independent companies involved with providing cybersecurity guidance, evaluations and equipment or remedies.”

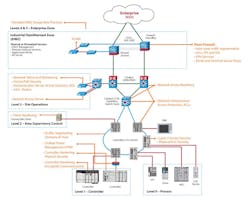

Figure 2: Setting up the industrial-control-system environment is the first step in designing a properly secured control system.

Many cybersecurity companies provide guidance to developers and engineers designing control systems, along with a variety of appliances that provide increasing measures of security, including plug-and-play devices that are designed to perform stateful packet inspection (SPI) for automation protocol networks, explains Clark.

“Many, if not most, control system applications are designed exactly backward,” says Clark. “They’re designed for functionality first, then for safety and then for security. We argue that this is exactly what causes the majority of security problems in the first place, especially when attempting to secure a working system, only to break specific functionality of the industrial control system (ICS), compromise the operational safety or create an unanticipated security hole down the road (Figure 2).”

Authenticate devices within the ICS to make sure that impersonation techniques don’t occur, especially for any legacy equipment or protocols. “We’ve provided a great deal of guidance in regard to setting up the application properly and interfacing with proper security and safety protocols required by customer IT security teams and possibly by regulation of the industry or vertical,” says Clark. “Firewalls using stateful packet inspection can be installed within the ICS along with appliances that establish authentication and authorization of the data to and from all devices, including legacy devices,” he explains. “ICS-specific routers should be installed and, if needed, products such as Lockheed Martin’s Industrial Defender can be used to monitor and control all traffic in the systems. These things are especially important when the network is unavoidably or inadvertently believed to be commingled with the business network.”

This level of awareness is usually discovered when assessing the cybersecurity readiness of the system by using a single-point-of-failure and gap analysis.

Doug Wylie, CISSP, director, product security risk management, Rockwell Automation recommends these layers for securing assets.

- Policies, procedures and awareness: Create a plan of action around procedures and education to protect company assets (risk management) and provide rules for controlling human interactions in industrial automation and control systems.

- Physical security: Document and implement the operational and procedural controls to manage physical access to cells/areas, control panels, devices, cabling the control room and other locations to authorized personnel only. This should also include policies, procedures and technology to escort and track visitors.

- Network security: An industrial network security framework is made up of network infrastructure hardware and software designed to block communication paths and services that are not explicitly authorized. Assets may include firewalls, unified threat management (UTM) security appliances and integrated protection within network assets, such as switches and routers.

- Computer hardening: Implement a patch management policy, install detection software, uninstall unused Windows components, protect unused or infrequently used USB, parallel or serial interfaces on any computer being connected to the industrial automation and control system network.

- Application security: Implement change management and accounting, as well as authentication and authorization to help keep track of access and changes by users.

- Device hardening: Restrict physical access to authorized personnel only, disable remote-programming capabilities, encrypt communications, restrict network connectivity through authentication, and restrict access to internal resources through authentication and authorization.