The distinction between vision systems used for inspection and those used for real-time control is blurring fast. All but the most basic vision systems are now equipped with digital interfaces that allow easy connection to the machine control system.

The control system uses vision system data to make decisions, either automatically or with operator intervention. These decisions often result in adjustments to the process that correct variations before they can cause rejects.

A number of trends are converging to increase vision system performance requirements in both inspection and real-time control applications.

Producing products in ever-smaller lots means manufacturers must be able to quickly and automatically tweak vision systems to effectively measure different product types. More stringent quality requirements continue to force manufacturers to replace manual inspection with automated vision systems. And high-speed manufacturing and real-time control often tax the processing speed of vision systems.

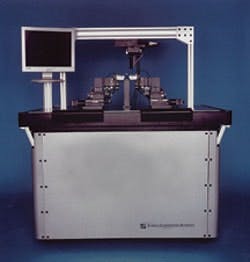

Figure 1: Sub-Micron Alignments

A vision system determines edge detection and part position for the alignment step in assembly of optoelectronic devices. These applications typically require sub-micron positioning accuracy. (Source: National Instruments)

There is also a definite trend toward moving vision systems further upstream in the manufacturing process. The intent is to identify problems as soon as they occur instead of at final inspection. This requires inspection of discrete parts as opposed to final assemblies, so vision systems for these applications must be inexpensive and easy to install.

Machine builders use advanced vision systems for many different reasons, but the overall objective is consistent. "At a high-level view, the goal of the vision system is to capture and process information," says Robert Pearcey, director of electrical engineering for Cookson Electronics Equipment (http://www.cooksonelectronics.com), Franklin, Mass. "The information is then converted into data that has value for the process." Cookson manufactures electronic assembly equipment for the SMT and semiconductor packaging market.

Let's Get Real Time

When vision systems are used as inputs to real-time control systems, tremendous gains in speed and precision can be realized. Palomar Technologies (http://www.palomartechnologies.com), Vista, Calif., upgraded a microscope targeting system from manual to fully automatic operation using machine vision. Palomar manufactures precision assembly systems including die bonders and wire bonders for customers in the wireless, photonics, defense, and hybrid semiconductor markets.

The company uses Cognex vision systems to enable rapid part location using flexible vision alignment algorithms. Palomar's customers choose from multiple automatic alignment options depending on the orientation and lithography patterns of their components. These can include area alignment, single point alignment, and pad-to-bump alignment.

One of the most important design decisions for machine builders using vision for real-time control is speed versus flexibility. "Opening up the process window to enable multiple part orientations or recognition of same-function parts from different vendors enhances program flexibility and reduces rejected parts, but may add costly time delays," says Eddie Wills, product manger for component assembly systems at Palomar. "Our integrated control and vision systems provide our customers with the ability to optimize their process window decision."

Stress Engineering Services (http://www.stress.com) also used a machine vision system to replace a manual system that relied on microscope targeting. Its precision integrated robot (Figure 1) uses a National Instruments vision system to perform edge detection and part position determination during the alignment process used in the assembly of optoelectronic devices. These applications typically require sub-micron positioning accuracy.

Automated vision systems can also be used to great effect when replacing systems that rely on hard tooling and fixturing. "Both manual and fixturing methods are costly in a high-mix or high-volume production environment," says Pearcey. "In some cases, it is not possible to develop the machinery or the process without the use of vision imaging and processing."

Vision systems on Cookson equipment are used to close the loop on positional feedback for alignment, inspection of deposited materials, surface coverage, and height measurements (Figure 2). The inspection of solder paste deposits on printed circuit boards is especially critical to reliability of the stencil printing process. Solder brick deposit images are acquired by the vision system optics and camera and translated into data for processing by the vision algorithms.

Figure 2: Positional Feedback Precision

Vision systems close the loop on positional feedback for alignment, inspection of deposited materials, surface coverage, and height measurements of solder paste deposits on printed circuit boards. (Source: Cookson Electronics)

There are areas where machine builders and their customers must pay particular attention when implementing a vision system. "It is best to consider the vision application as the equipment is being designed," stresses Pearcey. "The component to be inspected needs to be held within the focal range of the vision system, and process speed may affect the vision capture timing."

Real-time control applications add challenges to machine vision system design. "The application software of the machine must use the image data to make the proper determination to correct the process," concludes Pearcey. "This may call for an alignment adjustment, a pressure change, or some other type of manipulation of a control variable."

Pemstar (http://www.pemstar.com) of Rochester, Minn., uses vision system inputs to provide real-time closed-loop motion control for an adhesive attachment cell (Figure 3) used to align and attach components. Before the vision system was integrated into the cell, calibration of adhesive volume and position of the adhesive dispensing system was manual.

The vision system not only improves process quality, but also reduces the cost of other cell components. "Using the vision system to close the loop allows the motion control system to be lower cost," says John Martin, director of precision automation at Pemstar. "Adhesive calibration with the vision system means faster and more repeatable dispenser set-up. On-line measurement of alignment provides real-time control over alignment distribution."

Robotic systems also can use machine vision to close the control loop. Western Digital (http://www.wdc.com), San Jose, Calif., uses a Cognex vision system to locate a hard disk head stack assembly in a backlit shipping tray. A robotic gripper uses this location information to pick up the assembly and move it to a hard drive base.

The robot/vision system replaced an entirely manual operation, resulting in a substantial increase in speed and a reduction in labor costs. "The vision system quickly acquires the position of critical features and sends the data to the machine control system," says Andrew Klassen, a senior principal engineer with Western Digital. "The system is able to operate in normal factory lighting conditions because the camera filter is only sensitive to the red backlight under the shipping tray."

Visual Inspection Accommodates Uniqueness

Machine builders providing equipment to the automotive industry find the most demanding production environment is where complex products are produced in small lots. Automobile manufacturing is becoming more and more this type of environment, placing unprecedented demands on vision systems. Many automobile parts must be visually inspected prior to final assembly. In the past, customized inspection fixtures with inspection sensors were designed and built for each part.

This inspection method may be workable for high-volume production of standard products, but it won't cut it for low-volume manufacturing. "Customized inspection fixtures designed and built for each component contain vision sensors that sense the presence of components and features," says Ed Kachnic, president of Avalon Vision Solutions (http://www.avalonvision.com). "Our visual inspection system automatically loads the inspection criteria for each component, making it practical to inspect lot sizes of one."

Figure 3: Real-Time, Real Important

Vision system inputs provide real-time closed-loop motion control for an adhesive attachment cell used to align and attach components. (Source: Pemstar)

Avalon's QualityStation automatically identifies automotive interior components from bar code, serial, or Ethernet input; and configures the vision system for optimal inspection of each component. Configuration includes automated power zoom, focus, and aperture settings for up to 24 near-infrared cameras. The inspection system is also configured to perform different control functions based on the type of component.

The inclusion of automatically configured visual inspection systems with industrial machines lets an OEM provide customers the means to inspect a wide variety of components with one system. Production lines do not have to be designed to divert different components to custom test fixtures. This eliminates the expense of custom fixtures, and also simplifies the flow of parts through the manufacturing process.

The Need for Speed

The most important feature of a vision system for small lot manufacturing is flexibility, but the most important attribute of a vision system for standard product manufacturing is often raw speed. Standard products must be produced at very high production rates and must comply with stringent quality and consistency requirements.

Automated vision systems are replacing off-line manual inspection procedures in many of these high volume applications. DHAS Automation (http://www.dhasautomation.com) and InteWorx.Net (http://www.inteworx.net) jointly manufacture Matrix Trax, a high-speed, visual laser marking and verification system. Matrix Trax uses RVSI (http://www.rvsi.com) cameras to perform visual inspection and identification tasks.

End users can use Matrix Trax to replace manual inspection methods. "Before installing our systems, most of our clients could only collect limited information with a high incidence of error," claims Bill Glover, president of InteWorx. "Matrix Trax allows customers to automatically trace their products through the manufacturing process."

Jehren Industries (http://www.jerhen.com), Rockford, Ill., designs and manufactures assembly and test automation equipment using PPT vision systems. Jehren has built high-speed vision inspection machines for the fastener industry that are capable of inspecting multiple part characteristics at speeds to 1,000 parts per minute.

The primary tasks performed by Jehren's inspection systems include checking tolerances and dimensional features, sorting parts, and sensing the presence of part attributes and defects. "Before installing automated visual inspection systems, most of these tasks were performed manually, by the use of eddy current equipment, or not at all," says Scott Jerie, general manager.

In some applications, high-speed visual inspection systems must be upgraded to accommodate more stringent quality requirements. InSight Control Systems (http://www.insightcontrol.com) of Safety Harbor, Fla., manufactures inspection and data acquisition/control systems for plastic and metal caps used by the pharmaceutical and glass industries. InSight uses Coreco Imaging vision systems to perform a number of critical inspection functions.

InSight officials say many customers replace standard vision systems with custom-engineered systems. "Many of our clients were using off-the-shelf vision systems, but increasingly sophisticated closure designs and the constant pressure for increased throughput have rendered many of these systems obsolete," says Richard Hebel, Insight vice president, sales and operations. "Our systems use proprietary optical designs that allow great algorithmic depth even at very high production line speeds."

High speed and critical inspection requirements place extraordinary demands on vision systems. "Our machines can inspect 3,300 caps per minute, and that includes full color processing and print inspection of the consumer side of the cap," explains Hebel. "These kinds of capabilities blow away the traditional compromise of algorithmic depth versus throughput, and at these speeds our customers are able to recoup their investment sooner, without quality or yield compromises."

Mo' Better Quality

Machine builders that sell to manufacturers of safety-related components know that manufactured quality must be at the highest standards of repeatability. Automated visual inspection is often used to verify the quality of these products, as with a vision system manufactured by Ross Microsystems (http://www.rossmicro.com) and used to inspect fire sprinkler inserts. Ross specializes in on-line inspection and measurement of intricately shaped, non-fixtured products.

The manufacturer uses the Ross vision system equipped with Vision Components SmartCams to inspect metal inserts used in fire-suppression sprinklers. These inserts are manufactured in a variety of shapes, surface finishes, and diameters, and the inserts require inspection for correct part type, diameter, shoulder radius, metal shavings, and drill-slip surface damage. Dimensions range from 0.005-0.088 in., measured to a precision of 0.001 in.

This installation was complicated by a shortage of space for both the camera/light assembly and the necessary support equipment. The system was designed to accommodate all part types with a single camera/light configuration. The inspection system automatically makes algorithm modifications to accommodate different parts based on information received from a PLC.

Although the vision inspection systems designed by Ross are complex, the underlying hardware is composed of off-the-shelf components. "Over 85% of our new systems are centered around Intel processors and Windows NT," says Mike Leary, engineering manager at Ross. The fairly recent migration of our inspection systems to the WinTel platform has meant a startling reduction in overall system cost by significantly reducing development time and component costs."

Another area where consistent quality is a must is food processing. At the Keebler/Kellogg facility in Cincinnati, a machine vision system is used to verify quality for the production of 10,000 lbs./hr of crackers. Engineering firm Pak/Teem (http://www.pakteem.com) designed and installed a machine vision inspection system to detect improper alignment of 22 lanes of crackers moving from ovens to packaging lines.

The vision inspection system complies with baking industry GMP standards and is removable for maintenance and sanitation purposes. The system uses 12 Omron vision systems, 24 Balluff photoeyes, and an Allen-Bradley PLC and operator interface.

Many manufacturers are requiring their suppliers to comply with certain quality requirements, often to simplify their own operations. Delta Industrial Service (http://www.deltaind.com) designed and installed a vision system for a gasket manufacturer that measures distances with a DVT SmartImage Sensor camera and electronically records the measurement information. The manufacturer then sends this information along to its customer for further processing of the gasket material.

Electronic transmittal of this information eliminates the old manual operation and increases accuracy. "We are seeing trends in variety of markets pushing vision systems to be installed in upstream production," says Todd Kruse, electrical engineer with Delta. "This makes OEMs tolerances tighter, and also requires the collection of real-time data."

A Vision of the Future of Vision

Insight's Hebel sees a continuing move to smarter and faster inspection. "The simple, gross presence/absence inspection mentality is giving way to increasingly sophisticated algorithmic environments that sharpen the discriminant plane between various classes of image features," he concludes. "Defects will be named and robustly distinguished from process variations. This enhanced clarity will add value to the inspection data, and can also be used to close the loop on the manufacturing process."

The final home of the system also suggests a need for hardier systems. Jehren's Jerie finds many of the problems associated with vision technology are environmental issues such as lighting changes and intrusion by foreign particles such as dirt and oil.

The system designed by DHAS and InteWorx works well for most applications, but DHAS would like to see improvements to the hardware. "As manufacturing processes increase in speed and degrees of difficulty, advanced vision systems need to increase speed and performance to keep up with high-speed inspection and verification requirements," says Kerry Darnell, president of DHAS. "It would also be advantageous to have built-in communications ability for interface to PLCs."

Mark Bennett, PE, principal with Stress, agrees, reminding that, "image processing continues to consume a great deal of computing power, and I would like to see improvements in the efficiency of image processing routines along with improved lighting tools."

Pak/Teem engineers are content with their cracker-inspection system, but hope for vision systems that are easier to use and maintain. "Advanced vision systems could by improved by making them more user-friendly to the average plant maintenance person," says Kevin Jones, electrical systems engineer with Pak/Teem. "Vision is a specialized application, so there is a general lack of technical expertise with respect to the normal maintenance and operation of vision systems."

Leaders relevant to this article: