The resurgence of Spyder Manufacturing in Placentia, California, illustrates how the fate of a shop can be tied to its machine-tool investment decisions. It’s also the improbable story of how this second-generation company stumbled upon a business breakthrough: CNC that is intuitive and empowering (Figure 1).

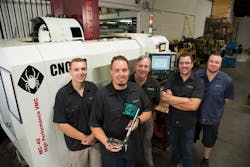

Figure 1: Gary Monnig and sons Justin, Matt, Nathan, and Jacob have revitalized their manufacturing operations by achieving game-changing returns on their CNC investments.

(Source: Spyder Manufacturing)

A second chance

Originally a manufacturer of lawn and garden parts and accessories, Spyder Manufacturing has been through several transformations. Once employing more than 30 people, the company experienced a sharp decline when global competition forced a downsizing of production, employees and profits.

Back then, Gary Monnig would often say that the machines owned by Spyder were so old and rudimentary that the company “maintained a stable of hamsters just to power them.” Spyder was spending thousands of dollars for outsourced machining, both locally and overseas, especially for more complex parts.

“There was nothing advanced about the shop,” Matt Monnig recalls. “So I asked my dad if I could look into how investing in CNC-based machining might revitalize our shop. He said absolutely, and, no more than five minutes later, entirely by coincidence, a CNC machine tool dealer walked in the door.”

A fever for change

Soon, a new Fryer MC40 milling machine, sporting a Siemens 840D control was delivered and installed on the company’s shop room floor. There it stood, awaiting the arrival of Fryer’s field service engineer to instruct the staff on its operation.

After graduating from high school, Matt had helped his dad run the company, but he had only dabbled in the machining side of things. “I didn’t know anything about machining when the new machine arrived,” he candidly recalls. “I didn’t even know how to turn it on.”

Not soon after, Fryer Machine Systems’ field service engineer, Trever Lowe, arrived to begin what was scheduled to be four days of training. However, almost at the outset, Matt Monnig said he was feeling lightheaded and nauseated and “needed to lay down for a little bit first.”

What they didn’t know was that Monnig had the flu. He was taken to a hospital emergency room, pumped with fluids and given two days of care. When he returned to the shop at the end of the week, he was ready to learn CNC machining. But now there were less than four hours of scheduled instruction remaining—hours that would prove to be a turning point for the company.

The power of intuitive CNC

Having earned a living as a tool and die maker, Trever Lowe may be among the last of a dying breed. He joined Fryer Machine Systems because he wanted to work for an American machine tool manufacturer. And he wanted to teach. One of his first assignments with Fryer was to travel to Spyder Manufacturing to teach Matt Monnig how to set up, program and operate their new Fryer machining center.

“When Matt returned to the shop after being hospitalized for two days, I realized that we had about four hours of scheduled instruction time left,” Lowe recalls. “So far, we had only walked through how to create tools and basically move the machine around. But now we’d run out of training time. So I decided to go right into the complex stuff—contour milling.”

Calling upon his many years as a machinist, Lowe understood that what his new student needed to learn was the one thing that every future machinist needed to learn.

“Today's machine tool and manufacturing market needs more than button pushers,” Lowe says. “Intuitive CNC is the first step. Fryer Machine Systems machines enable the machine operator to shine. They can start to write their own programs at the control. Other companies try to compete in the conversational market, but Fryer Machine Systems chose Siemens CNCs because they are truly intuitive, first and foremost.”

When learning to program a Fryer machine, if you can understand the complex stuff, then in time you will figure out the simpler stuff, Lowe concludes. “So that’s what I did. In less than four hours, I showed Matt the most complex programming.”

In the span of a few hours, Matt needed to learn to use a CNC machine for the first time. Not only that, but he was learning on one of the world's most powerful controls, the Siemens Sinumerik 840D, to program complex contour milling, right at the machine.

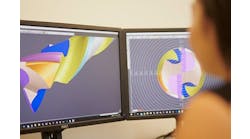

"After those few hours of training, I left with doubt in my mind. I figured nothing would work, that he would crash the machine and it would be a complete catastrophe,” Lowe recalls. “But that’s not how it went. It went completely the opposite. Ever since, when customers ask me how much training time is needed on one of our machines, I tell them we schedule 16 hours. Then I tell them about Matt, someone who didn’t know anything about CNC, but who in less than a day picked up enough CNC know-how to relaunch his business (Figure 2).”

Figure 2: Matt Monnig programming contour milling at the machine using machine step programming.

(Source: Spyder Manufacturing)

Programming at the machine

Ahead of Lowe’s arrival, Matt was a restless student in waiting. Influenced by conventional wisdom, he had invested more than $4,000 in CAD/CAM programming software.

“I bought and trained on the software,” Matt admits. “But I never used it, because it turned out that the Siemens control has something called ‘conversational programming.’ That’s what Trever showed me during our short training session. I just found it so much easier to understand and to work with than the complicated off-line software.”

Lesson learned, say both men. The ability to program at the control brings a competitive advantage to a shop. It empowers both the operator and the shop owner to efficiently produce more than they could otherwise. Instead of waiting for a CAD/CAM programmer to feed a G-code program to a machine, an operator can quickly set up the next program and keep production rolling.

CNC-driven innovation

Spyder Manufacturing is also the story of how a greater return on CNC can mean a greater return on a shop’s workforce, enabling a business to leverage the skills and knowledge of its people to create new opportunities for the company.

Matt Monnig recalls how, from the earliest days of the company, Edward Jones was an especially resourceful machinist. Called upon for his hands-on perspective, Jones found ways to create new product ideas, using whatever were the tools of the day, long before the dominance of CNC machining.

As Matt recounts, “Not long after we bought our first Fryer machine, I drew up an improved version of our climber product. But the immediate feedback I got was, ‘No. That will never work.’ But then I showed the sketch to Edward, and he said, ‘Let me make a sample.’ And so he handmade a sample, and we looked at the tools and what the new Fryer machines could do, and we all said, ‘Wow, that will work.’”

The new product design was soon validated by the CAD/CAM capabilities of the Siemens control. Using highly intuitive, graphically guided functions such as the contour calculator, the shop could readily conduct design for manufacturability refinements right on the machine. And at the same time, they were establishing the program to produce it. With no G-code language barriers in the way, the shop could conceive, design and produce a new generation of products (Figure 3).

Figure 3: With no G-code language barriers in the way, the shop could conceive, design and produce a new generation of products.

(Source: Spyder Manufacturing)

Optimizing resources

Today, Spyder Manufacturing is a company transformed. For Gary and Matt Monnig, achieving a greater return on their CNC investments includes taking greater control of their business, enabling their people and operations to become increasingly efficient.

Now the company produces parts for customers overseas, rather than the other way around. Spyder is also able to bring next-generation products to market and efficiently keep pace with the demand for those products. Including products made possible by bridging old-world machinist skills and knowledge with creative leadership to capitalize on the most intuitive and powerful CNC available.

“The Fryer machines have paid for themselves many times over,” Matt Monnig says. The company owns three Fryer MC40 milling centers, all equipped with Siemens Sinumerik 840D controls.

Before the company’s investment in Fryer and Siemens, it took the shop a month to produce 50 sets of tree climber products. Now the shop produces nearly 500 sets each month.

Higher production capacity and efficiency have brought a near tenfold increase in the sale of the company’s flagship product, the same product whose evolved design was first thought never to work.

Looking back, Gary Monnig and his son Matt consider themselves fortunate to have stumbled upon the best possible strategy for revitalizing their business. Looking ahead, they plan further investments in Fryer-Siemens machines, knowing that anything is possible given the right set of circumstances: the managerial desire to ask what if, the strength of a machinist’s imagination to see the way, and the power of intuitive CNC to make it happen.