While not your typical, grey-metal industrial automation application, industrial strength controls are needed to raise and lower custom lighting pieces onto the TV studio stage set. At Showman Fabricators, a studio set designer/builder, we created a solution that controlled and configured 20 separate servo motors that were mounted on the ceiling, 25 feet up.

What made this a difficult application was that, for each automated lighting/scenery configuration, 20 separate motors and their programmable logic controllers (PLCs) needed to be reprogrammed over USB, using PC software. Making the matter worse, USB communication is a short-range, maximum16-foot connection. The use of a laptop—on a scissor lift—every time a change had to be made in the studio set was unacceptable.

Stagecraft solved this problem using SEH Technologies USB device servers to connect serial devices, the integrated servo motors, over a TCP/IP network. This gave show set designers and other industrial automation providers more options when mounting these servo motors and other USB communication devices in hard-to-reach places.

Setting the scene

When we talk about industrial automation, we tend to think first about such things as factories and oil pumps, not entertainment. But the electrics team at Showman Fabricators makes what I like to call “the weird and the wonderful.”

Founded more than 30 years ago, Showman Fabricators designs and creates custom sets and environments, using all kinds of materials and shape-building techniques. Whether it’s the glitzy set of a TV show or a Broadway play, a replica of an historical street in a museum, or a unique retail or public space, this company builds 3D structures, as well as associated electronics, graphics and mechanical parts in a state-of-the-art facility in Bayonne, New Jersey.

Showman is riding a wave of innovation in theater technology. In general, this is due to developments in industrial automation including IP-enabled motion control and 3D printing. An example of this innovation can be found in an automated scenery system we created for a new TV studio in New York City. The project involved 20 ClearPath integrated servo motors from Teknic. Each motor was used to raise and lower an illuminated scenery piece. Adjusting the elevation of the set lights is common function as it changes the size and the feel of the set, as seen through the camera.

Motor control, setup, monitoring

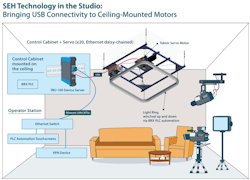

Hanging from the studio ceiling 25 feet up, the servo motors hoist these scenic elements—large light rings containing LEDs that shine in multiple colors—on command to specified positions above the studio’s floor. These positions are pre-programmed into PLCs, the brains behind many industrial automation systems. The commands are sent over Ethernet, strung up into the ceiling, from the stagehand’s touchscreen operator station at floor level to the motors above (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ceiling-mounted servo motors with USB connectivity over Ethernet raise and lower lighting elements in the new studio using an automated system run by PLCs. (Source: SEH Technology)

The integrated servo motors must be calibrated, monitored and programmed through Teknic’s ClearPath motor setup program (MSP) software running on a PC. This PC-to-motor communication is needed to commission and tune the servo motors with such parameters as the weight of the scenery element they lift, which may change. And that, in turn, requires a one-to-one USB connection, with a cable length limit of 16 feet between PC and servo motor. The ClearPath software is also used for system monitoring and possible troubleshooting, to ensure the precision of those positions and movements.

Problems working above the scene

Manually plugging each of 20 ceiling-mounted motors into a PC via a USB-cable connection, presumably while standing on a scissor lift, was not going to work. The only practical way that the Showman Fabricators team could efficiently tune servo motors that were mounted on the ceiling was by simulating that direct USB connection over the existing Ethernet network.

This was only the second project in which we used these particular servo motors. In the previous project, the motors were installed at floor level, so accessibility was not an issue. This is the first time we wanted to put them up in the air, which led us down this design path.

That path led me to a PLC-programming discussion forum, where I picked the brains of generous fellow engineers. I asked forum members to recommend a solution with crash-resistant software, as rebooting devices hanging from the ceiling to reestablish connectivity was also a non-starter. I also required easily customized addressability, so that each of 20 devices would have logical and easy-to-understand names. The control system already had a 24 Vdc supply I also requested a solution that required no separate supply and that was DIN-rail mountable.

We needed a way to communicate over Ethernet with the servos, so we needed to do USB communication over our Ethernet TCP/IP network, which is how I posed the problem. Ethernet was a logical choice for us, as we already had a network in place for PLC-based control of the automation system.

Forum responders came up with several USB device servers for me to try.

A connected solution

SEH Technology’s INU-100 USB device server was chosen for several reasons. Importantly, they were able to confirm lead time for a relatively large quantity, 20 units. Equally important, test samples are a standard service at SEH, something other vendors were unwilling or unable to provide.

SEH Technology sent a sample INU-100 for testing with the servos. This was critical, as Showman management wouldn’t commit to purchasing 20 USB device servers with the chance there would be incompatibilities. Testing was needed.

I set it up on the test bench with my laptop and had the thing talking to the servo in about 10 minutes. The servo’s USB port was cabled to the INU-100, and the INU-100’s Ethernet port to the existing Ethernet local area network (LAN) switch. Then, using the software tool, SEH UTN Manager, to establish, manage and organize access to the USB device, the motor was assigned a meaningful, friendly name.

Testing showed the INU-100 USB device servers from SEH Technology worked well converting USB communication for transport over Ethernet, and testing proved it worked with the previously installed Ethernet network used by the PLC and human-machine interface (HMI). It’s nice because I can have 20 of these things sitting on the network and just talk to the motor that I need to set up. I’ve played with a couple of other device servers over the years, and these were certainly the most user-friendly to set up and very stable.

Fabricating the solution

Our automation & electrics department team built a Showman-Fabricators-branded control cabinet, called a Light Ring Winch Controller, for each of the 20 servo motors (Figure 2). Each cabinet exterior is also labeled with two IP addresses: one for the PLC controlling the motor’s routine operation and one for the USB device server for configuration and programming of the servos.

Figure 2: For each of the 20 scenery-lifting motors, Showman Fabricators assembled this light ring winch control cabinet with external controls, which also includes two internal control panels. (Source: SEH Technology)

Each double-sided cabinet, built with a center backplane for compactness and serviceability, houses all the control hardware. One back panel contains the motor power and configuration hardware, as well as the scene light control (Figure 3). This includes the motor braking resistor, LED dimmer, power supply, circuit breakers and the INU-100 device server that bridges the integrated servo motor controller’s USB port to the Ethernet TCP/IP network and then its ClearPath MSP software installed on a separate PC.

Figure 3: The back panel contains the motor power, LED dimmer and configuration hardware including SEH Technology's device. (Source: SEH Technology)

The other side of the light ring winch controller cabinet contains the PLC that directs the motor to move the lighted scenery and related control relays and power supplies. It also includes an Ethernet switch.

Figure 4: The back panel contains the PLC and network hardware that directs the winch motor to move the lighted scenery. (Source: SEH Technology)

We used AutomationDirect BRX PLCs and Teknic ClearPath servo motors communicating via Ethernet. The externally mounted ClearPath servo motor is an all-in-one, compact package that includes a matched motor and drive.

A key piece of control hardware was the SEH Technology product that converts USB signaling for transport over Ethernet TCP/IP. As noted, while the servo motors can be controlled by the PLC via Ethernet, to bring the motors’ USB connectivity for configuration and programming from the ceiling down to stage level, we installed INU-100 USB device servers from SEH Technology into the control cabinet of each motor.

I can easily foresee future orders for more such device servers, as freedom from scissor lifts and the possibility of remote access using a VPN gives me added design flexibility for future projects involving moving parts or other USB-accessed hardware.

This is especially true if we use these Teknic servo motors again and need to mount them where they’ll be inaccessible. I can definitely see us using the device server again. Just being able to talk to the motor over a network without having to be directly attached via USB to it or the control cabinet is very helpful for us.

ALSO READ: Simplify press maintenance and management through IIoT innovation

About the Author

Ryan Poethke

Showman Fabricators

Leaders relevant to this article: